Harry Gregson-Williams on Scoring Gladiator II

SPECIAL EDITION ISSUE 03

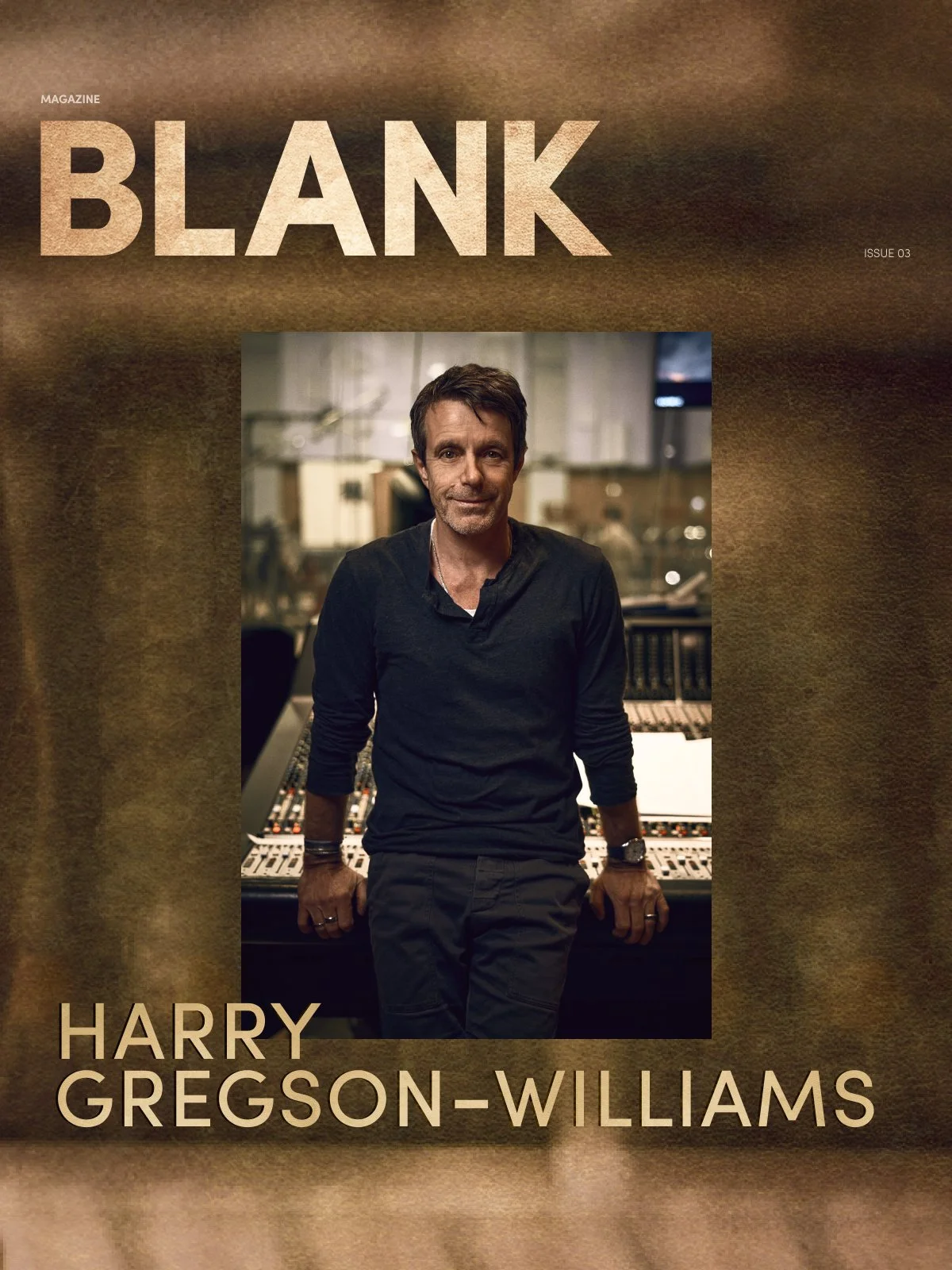

Nearly 20 years after first working with director Ridley Scott on 2005’s Kingdom of Heaven, Harry Gregson-Williams took on a project with an even longer history.

Words by Owen Danoff

“It’s terrifying,” composer Gregson-Williams says of the drive for new challenges that led him to score Scott’s long-awaited Gladiator II. Not only was the film a follow-up to a movie Gregson-Williams didn’t work on, but it would also force the composer to step into the shadow of his former mentor, Hans Zimmer, and write roughly 90 minutes of brand new music for the film. After consideration, and a call to Zimmer not unlike a request for the composer’s blessing, Gregson-Williams decided to step into the arena.

Gregson-Williams pulled from the legacy of Maximus but ultimately strove to create his own take on the sounds of the Roman Empire. This involved a trip to northern Spain to work with an instrument maker skilled in approximating Ancient Roman instruments, as well as collaborations with other unique soloists to craft a grand and intimate sonic language fitting the film’s epic yet emotional tale. Read on to learn how Gregson-Williams built his sonic palette for Gladiator II, how Hans Zimmer’s themes fit into the sequel, and what Ridley Scott is like as a collaborator.

How would you describe the sound of this score, and how did you go about creating that sound?

Harry Gregson-Williams: I think it's fairly eclectic. Who's to say what the sounds of ancient Rome should be, could have been, or would be?

Part of the job of doing a score like this is putting together the sonic palette. I collected several instrumentalists, soloists, and vocalists to bring a sound together. It’s always fun to do that—to begin, before actually writing a note, by surrounding myself with players and sounds that are going to inspire me.

On this particular occasion, I found a multi-instrumentalist, Abraham Cupeiro, who actually made his instruments—instruments that could be perceived to be about as close as you get to what they might’ve been in Roman times, based on pictures, paintings, and literature. They were made out of various animal horns, and shells pulled from the sea, all quite crude and rudimentary instruments. I went to visit him in northern Spain with a couple of cues written, had him play all over those two cues, and then brought that back to my studio here and picked away at what we'd recorded that weekend. That formed part of my template.

I recorded two instrumentalists who I've worked with a lot and who have played on many of my scores, an electric cello player and an electric baritone violin player. They’re both fabulous players, and their instruments do specific things that I can’t get from a conventional violin or a conventional cello.

As concerns vocalists, I searched high and low for unique vocalists and found some wonderful singers. I had a vast choir that I recorded at Abbey Road in London, but I really wanted to find some soloists who gave certain flavour to various characters within the film. I found this wonderful singer called Lior Attar—he’s an Australian singer-songwriter, but he sings falsetto—and I managed to weave him into the score. There was a Nigerian gentleman who puttered up my stairs here at my studio in Los Angeles, a chap called Ayo Adeyemi. He sang some bits and pieces I cut up and treated, and I think we hear those at the beginning of the film over the chieftain of Numidia. They’re together with Lisa Gerrard (Note: Lisa Gerrard was a soloist featured on Hans Zimmer’s score for the original Gladiator). I called Hans Zimmer quite early on, just after Ridley called me, and asked him how he felt about me maybe involving Lisa. He said, “Just go ahead and ask her. I'm sure she'd love to do it.” So, Lisa sang on a couple of bits in the film.

“One of the challenges was to find a way of bringing the DNA and the spiritual essence of the first movie and its score into our story.”

One of the challenges was to find a way of bringing the DNA and the spiritual essence of the first movie and its score into our story without quoting it verbatim or leaning on it too heavily. Lisa was key to that in a couple of spots. It seemed perfect to bring her very unique artistry to things right at the beginning of the movie. In fact, before the movie even begins, we’re on the Scott Free logo, I think, and we hear Lisa’s spiritual vocalisation. Then, there’s a place toward the end of the film when Lucius discovers Maximus’ sword and shield underneath the cells, and it seemed like a great place to call back to Lisa.

I used Hans' main theme for the first Gladiator in a couple of spots as well. There was one very obvious place where we see Maximus—there’s a flashback—and I quote a little bit there. Then, it’s at the very end of the movie Lucius is becoming the hero he needs to be.

When we first meet him he's living a quiet life, by the looks of it. He’s quite a simple chap, but he becomes the guy we need him to become during the course of the film. Consequently, the thematic material I wrote for him contains a nod to Hans’ theme, but it’s a fresh piece of music. Probably 90 minutes of music is completely new for this film.

As the story progresses, I hope viewers will begin to feel that Lucius’ theme from the beginning of the film kind of becomes Maximus’ theme toward the end of the movie. In fact, in the script, there was a line which said, “It’s at this moment that Lucius becomes Maximus.” And that seemed to be a place for my theme to evolve and become the main theme of the first movie. So, that was really what I set out to do, but you’ll have to see whether you think I achieved any of that.

That’s interesting, what you said about evolving his theme as the film goes on. What kinds of things did you find yourself changing? Is it more instrumentation or melody, and did that feel like you were breaking any rules?

Harry Gregson-Williams: No, not at all. You know, this is a sequel. I’ve done plenty of sequels. I’ve done the Shrek franchise, The Chronicles of Narnia, The Equalizers—but there’s a big difference here. I did the first Shrek. I did the first Equalizer. I did the first Narnia movie. I didn’t do the first Gladiator. But there was no reason not to enhance whatever I could bring to this story and give the audience what they expected to want toward the end of the movie.

As I say, Lucius’ theme isn’t based on Hans’ theme. It’s actually, shall we say, a first cousin once removed. It contains a couple of elements that Hans hasn’t got a patent on. There’s a descending seventh figure that his theme utilises, and I grabbed a hold of that and wrote my own theme.

Part of Lucius’ theme, which isn’t a heroic thing, is what I think Ridley called the DNA theme. It’s the DNA of Gladiator—Gladiator I and Gladiator II. It’s a high ethnic flute sound, a small figure, a simple phrase, reflecting Lucius’ character when we first meet him. It also almost pulls him towards his mother. We hear it intermittently in the first two-thirds of the film. It’s almost like a memory for him. It’s something that binds him to this Gladiator hierarchy. That was actually played by another old boss of mine, Richard Harvey, who’s a wonderful instrumentalist.

ISSUE 03

“We, as composers, have one chance—and it’s the first time a director hears your music.”

HARRY GREGSON-WILLIAMS

How do you work with people who are proficient at instruments that you might not have a background in? How does that affect your writing?

Harry Gregson-Williams: It doesn't really affect the writing. For instance, there's a consort of viols, basically a viol quartet. They’re the precursors to the instruments that we find in the modern-day orchestra—the violin, viola, and the cello. They look similar, but they have a different amount of strings, they’re played in a different way, and they have quite a cold tone. It’s not a warm sound.

Now, have I ever played a viol? No. Do I know the range of a viol? Yes. I’ve researched that. I used the same consort of viols—they call themselves Fretwork—on Kingdom of Heaven, which was the first movie that I did with Ridley, many years ago. I really wanted to deploy them for their rather frigid and icy sound. There’s nothing rich about them. It’s quite a mean sound, and it gives us the feeling of something quite ancient.

There’s a track called “I See Him In You”, which is a conversation Lucilla’s having with Lucius. I didn’t want the warmth and grandness of the orchestra in that particular scene, so I shrunk down the orchestration and the arrangement to this consort of viols.

With some of these instruments that I recorded and sampled in Spain with Abraham Cupeiro, I brought the sounds back to my studio and put them on my template. I was able to use them in any way I wanted to, and I didn’t have to be able to play them other than with my fingers as if they were on a keyboard. I wasn’t blowing ancient horns or conch shells.

With a vocalist, for instance, I’d bring them into my studio and give them an idea. I might sing to them the sort of line I want them to explore, or have that written out if they read music. There was a santur player, Hamid Saeidi—the santur looks like a harp set on its side, and it’s played with soft hammers. He reads music beautifully, so I was able to be very specific about what I wanted him to do. With another instrument, I might let the instrumentalist improvise a little bit, and I’d understand a bit more about what they could bring to the music.

Are you then adding in the orchestra later?

Harry Gregson-Williams: What I tend to do with the featured soloists of the score is, write their parts and record them during the demo process. So, I'm writing a cue to picture here in my studio, and then I'm adding these flavours as I go along, before I even play the music for Ridley Scott. I'm being expressive, as far as I can be, with how I might deploy some of these ideas. Then, I'll play a cue for Ridley to picture, and he'll react to that.

He's a really visual director. He's a painter, first and foremost. He paints all the time. It's great with him. He speaks to me as if he's speaking to me about my painting, although he's speaking to me about music. He's talking to me about tone and colour and texture—"I feel this could be a little darker here,” or “It could be a bit more abrasive there.” He could be talking about a canvas. He might say, “What would it be like if we had a little bit more pace here,” or, “Could we have a little bit less warmth here?” He’s not directing me musically, but he's pointed to me on a path that he wants me to go.

“To this day, if I can, I'll meet with my director in my studio, certainly for the first few playbacks. There’s nothing quite like reading body language and being in the same room as someone, and it's an environment we can control.”

You recorded the orchestra at Abbey Road, where I know you’ve worked many times in the past. Is there something about that space that you feel lends a certain characteristic to your scores?

Harry Gregson-Williams: There’s something magical about that space. I feel very connected to it personally. Many years ago, before I had come to the States and really begun to score films, I assisted composers who recorded in Abbey Road, so I would be an assistant in the back of the room, listening carefully, watching what was going on, and admiring this beautiful sound that could be created, it seemed as if by magic, in that big room—Abbey Road Studio One.

Little did I know, many years later, I'd return there with my own music. It’s a great joy. There’s nothing more thrilling for me than the first day in the first session on the first day of recording.

In this instance, I recorded a cue called “Strength and Honor”. I usually record a meaty piece of music without the picture, without headphones, without click tracks, and without any bearing to anything else, just to give the orchestra a chance to really get to know what I'm trying to do. It’s thrilling. It's a beautiful place to record, and there's such history there as well.

I remember doing a movie for Ridley's brother (Tony Scott), Spy Game. I was in Studio Two doing it. We had tried to get Studio One, but there was somebody else in there—he was called John Williams, and I think he was doing Harry Potter. So, there is a pecking order. I remember seeing him in the canteen and thinking, “Oh my God. I wish I had time to be listening to what he's doing.”

The nightmare scenario must be sending something you’ve worked so hard on to somebody and having them listen on their phone speaker.

Harry Gregson-Williams: Well, yes. I'd done a couple of films that Ben Affleck had directed. He came to see me here in Santa Monica at the beginning of Live by Night, and he was surprised. He said, “Look, I’ve got to leave. I’ve got to go and be Batman. I’ve got to go to London for about five months.” I said, “Hold on a second, Ben. We’re not even nearly done with the score here,” and he said, “Well, I've got to go.”

I said to him, “Listen, man, I'm going to send you music. Please don't be listening to it on your laptop, for goodness’ sake.” Before he left, I called my recording engineer and said, “What are the best headphones on the planet?” He told me. I was a bit shocked at the price of them—two or three thousand dollars. I went, bought some, gave them to Ben, and told him, “If I send you music, please listen on these. Promise me you'll listen on these.” So he did. It turned out he made a few trips back, so we did have meetings in the same room, but if needs must, you’ve got to take radical action. That was my way of hoping he would listen to my music in the most favourable way possible.

You’ve done such a range of things, and you said you’re taking on fewer projects than you did when you were starting out. What’s appealing to you when you think about your future projects? What kinds of things would you like to do?

Harry Gregson-Williams: I think doing anything that I haven't really done before. Gladiator was one of those. I haven't done a Gladiator movie before—I certainly didn't do the first one—and that's fascinating. That’s where the juice is. It's terrifying, also. It’s quite inhibiting. It made me feel quite vulnerable, doing a sequel to a Hans Zimmer score. But that's essentially what we live for.

There are so many genres that I haven't tackled and there are some that I have that I think I could do better if I had another opportunity. I’m always looking to challenge myself and I don't have to look too far. I find it's all pretty challenging, but that's kind of why I love it.