ISSUE 02

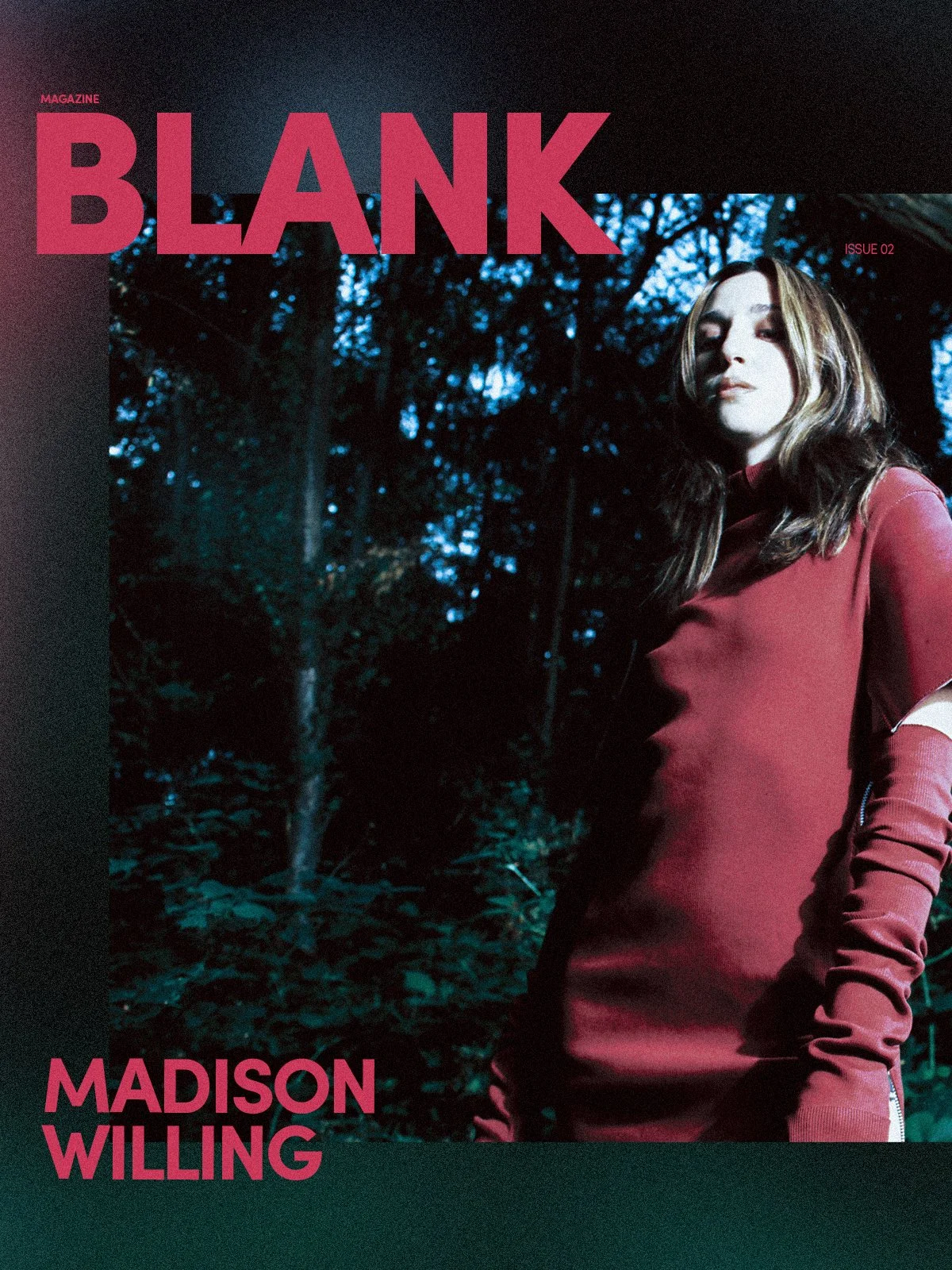

Madison Willing on her Debut Record Birth LP, Empathy & the Future of Composition

The composer and producer discusses her debut record Birth LP, her journey from DJing to media composition, and why empathy should play a bigger role in the music industry.

It’s a rare sunny morning, and as the light streams through my windows, I’m waiting for Madison Willing to join our call. I’ve just finished listening to Birth, her 10-track debut solo LP. It’s a bold and assured statement of her artistic vision, expansive and cinematic, yet grounded in an intimate, deeply personal tone. It’s also a record that allowed her to process and navigate the challenges life threw her way during its creation. There’s something that I find deeply admirable about an artist transforming that energy into something others can connect with.

When Madison appears on screen, she admits she’s not much of a morning person but reassures me she’s ready to go after her second coffee—a sentiment I can relate to. She gives me a quick virtual tour of her studio, spinning her laptop to reveal a cosy, gear-filled space with an essential creative touch: a window framing an East London street, its trees glowing with autumn’s golden hues.

Over the next hour, we discuss the meticulous process behind Birth, her journey from DJing to media composition, the artists who inspire her, and—perhaps most passionately—why empathy needs a larger role in the music industry. Madison’s enthusiasm is infectious, and her perspective is refreshing. She’s a composer who should be on everyone’s radar and one I hope to see on many film and TV credits in the future.

Your new record Birth LP has just been released! How are you feeling?

Madison Willing: I feel a mix of relief and excitement. It's a big body of work, so thank you for acknowledging that. With this project, I wanted to create my own visual landscape to work from, almost like setting my own brief. In film scoring, I'm always responding to someone else’s brief, but this time, I built a world in my mind and lived in it. That was incredibly fulfilling, and I'm eager to share it.

And now, with the music video, I was able to reverse my usual process. It’s a response to the imagery I created, turning the music into something entirely personal, like a piece from my diary. It’s exposing, a bit scary, but so satisfying—like scratching an itch I’ve had for a while.

Your track, Thinking of You, reminded me of Cliff Martinez's work in Drive. It had that continuous, propulsive feeling. Could you walk me through the creative process behind this record and what you were hoping to achieve?

Madison Willing: This album was really about expansion. A lot of it actually comes from fragments of pieces I’d written for films that didn’t make the final cut. I took those small ideas and turned them into longer, more linear compositions. For instance, cues that might only last a minute or two in a film, I extended to six minutes to allow them to live in their own sound world.

I wanted the album to feel like a continuous experience with its own timeline, unrestricted by picture. I love how composers like Cliff Martinez, Trent Reznor, and Atticus Ross build energy with minimal shifts. It’s almost like each track exists in a different sound world, building an atmosphere in a way that’s unique from traditional “Mickey Mousing” in film scoring.

One track, Falling, is a good example. It has a repetitive, minimal piano riff with elements of sound traffic layered in—kind of like a scene in a Michael Mann movie. Each track on the album has its own feeling and energy, but together they create a linear journey.

The album is designed to be a 35-minute emotional arc. I wanted listeners to feel confronted by themes of anxiety, darkness, and uncertainty, but in a comforting way. It’s therapeutic—almost like watching a movie where you can explore these heavy emotions in a safe space. I think of Spielberg’s work, like in The Fabelmans, where he tackles difficult subjects, yet presents them in a way that makes you want to keep watching. That’s the essence I wanted to capture with this record.

“When you let those clean, aspirational strings respond to something dirty or gritty, they interact in a way that feels alive.”

Are there any standout tracks on the record for you? If not, that’s fine too.

Madison Willing: Definitely. The track Birth stands out. In the lyrics, I’m saying, "I can dance, I can open up all of your doors, I can dance in the rain." The words are hopeful, but they’re set against a dark, grungy backdrop with cold, beautiful strings and a beat that dBridge added. It reflects the paradox in relationships, where you open up completely, only to have someone take advantage. I went through that—letting my ex live with me, and feeling like he was poisoning my space. Birth was the first track I wrote after our breakup.

Another personal track is Thinking of You, the first piece I wrote after my grandmother passed away. She was the matriarch of my family, the painter Paula Rego, and she taught me that being deeply personal in your work can resonate universally. I wrote it in just two hours, and recorded it a week later, and that raw, instant energy is what’s there in the track. If I’d over-polished it, I think it would have lost that meaning.

Let’s dive into the technical side of the record—what went into creating the sound, and who helped you bring it to life?

Madison Willing: Sure! I wanted this record to feel very personal and intimate. It’s like a one-player game—you experience it alone, and it’s inward-focused. I’d like my next record to be more outward, with big orchestral layers, but this one is intimate, almost like a chamber piece. I only used a couple of players, like a violinist and a viola player, and multitracked them. I also recorded myself on piano and laid down synth lines with my Korg, which gives it that hybrid feel, similar to Ólafur Arnalds’ sound.

I used a mix of samples and live players, which is rare. Usually, people strip the samples out at the end, but I kept them. I used samples to create a muted, distant, and cold sound and I think this helped build this moody foundation that I then layered with the more expressive parts. It’s a big reason why the album has this gloomy, blue tone.

“It’s about discovering unexpected sounds and collaborating with people who are pioneers in their fields.”

You brought in live players. Where did you record with them?

Madison Willing: Well, I actually did all the multitracking remotely because it was during COVID. I couldn’t get a space to record, so I made the whole album about two years ago. Working remotely ended up giving me more control, I could direct each line and add layers. I like that kind of control in scoring as well, where I can record a single string line, play with audio effects, and then bring it back into the final session to add some edge. It adds a bit of dystopian texture to the elegance of the playing.

It’s similar to what Ben Salisbury and Geoff Barrow do. They record a clean track, then add effects and layers. I don’t always go back to re-record; I keep a project for the “messed-up” version and another for the clean. Then, in the final mix, I layer them together, blending the clean sound with the more granular, textured elements. That contrast where something very polished sits alongside something a bit "fucked up" creates an interesting tension that I love.

When you let those clean, aspirational strings respond to something dirty or gritty, they interact in a way that feels alive. I love getting a rough beat from someone like dBridge and then layering it with these aspirational strings. That contrast is what excites me the most.

Could we step outside of your record for a bit and talk about your work as a producer and DJ? I find it really interesting, especially with more crossover into media composition. It’s exciting because it brings different perspectives and attitudes to scoring, which I think is so necessary now. How are these experiences in your career shaping your work as a composer for film and TV?

Madison Willing: I think instead of transforming, they expand my approach to new projects. Being a DJ and producer widens my relationship with the material. When I start on a film, I can come at it from a unique angle. For instance, maybe we need something unexpected, it’s like a film school exercise where you plan for a disco score but then try rock, and it completely shifts the picture. That kind of unpredictability keeps things fresh.

As a DJ, you’re always finding new sounds and responding to different settings, whether it’s a house night or a dark, grungy techno night at Fold. It trains you to read the room and adapt, and I think that’s really useful in film. When I start on a project, it’s about capturing the immediate feel. I like to keep it flexible, even if that means spending months discussing the vibe with a director and then changing the genre entirely by the end. Some briefs are more rigid, but the DJ side of me enjoys the unexpected, not just sticking to one style or being “cool.”

It’s about discovering unexpected sounds and collaborating with people who are pioneers in their fields. Working with legends from Exit Records, for example, is inspiring—they’ve spent 20 years building an underground drum and bass legacy. I wasn’t even a drum and bass DJ; I was into ambient techno and had my years in Berlin, immersed in ambient sound design. But that’s also why I chose to release a modern classical album on a drum and bass label. It’s unexpected, but that’s the point. People might ask why, and it’s simply because Exit Records has been pushing the boundaries of dance music for decades. So, why not?

Since you’ve focused more on that space from the start to now, how do you feel your sound has grown or changed over time?

Madison Willing: I think it’s grown in an interesting way. Recently, I watched an interview where Andrew Garfield talked about how David Bowie had different personas, and that really resonated with me. I think scoring has allowed me to adopt different personas as well, kind of like actors taking on new roles. Each film lets me live in a new musical world, flexing a different creative muscle without it being about me personally. But now, I feel like I’m finally finding my own persona—this darker aesthetic that’s been in development almost unconsciously.

People are often surprised when they meet me because they expect something different from my personality. I’m smiley and talkative, but my music taps into a different, darker side. In a way, scoring has helped me assume that character, and now I’m embracing it more in my own work. I want to take that persona onto the stage and express it in new ways, even if it’s a bit outside my usual comfort zone.

I want to talk about empathy, which feels relevant to everything we’ve been discussing. How does empathy play a role in your approach within the industry, especially in interactions with collaborators, peers, and even fans?

Madison Willing: Empathy is at the heart of it all, I think. In scoring, we’re empathising with the characters on screen, and that sense of understanding extends to working with peers. It’s about making space for everyone to have a voice. My live performances or projects don’t need to disrupt anyone else’s. Empathy is about giving others patience and space to express themselves.

I remember Martin Phipps once saying it’s surprising there aren’t more female composers since empathy is such a natural fit for that line of work. It allows for a unique kind of expression, one that’s personal and meaningful. That’s why I named my album Birth—it’s my own “birth” as an artist, something deeply personal and born of my own hard work. My hope is that it inspires others to find and share their voices, too.

And I’ve realised that there doesn’t have to be a “cookie-cutter” way to be in this industry. Why box myself in as just a composer, a producer, or a performer? I can direct a film or release an album, and none of it diminishes my work in any other area. I think now, I feel at peace with not defining myself too rigidly. It’s freeing.

Let’s look to the future: the music industry is shifting with all sorts of changes, and technology is a big part of that. Without going too deep into AI specifically, I’d love to get your thoughts on the changes you hope to see for composers in the years to come.

Madison Willing: It’s really about composers feeling confident enough to develop their own voices. Technology is allowing more people, including women and non-binary folks, to explore live music, scoring, and other creative avenues.

I don’t feel threatened by technology; it’s a tool that can help us focus on creativity instead of getting bogged down in the technicalities. Moving forward, I see composers becoming tastemakers, not just technicians. It’ll be more about self-expression within the mediums we have, which is why I encourage other composers to develop their own albums, perform live, and embrace all aspects of their artistry.

Technology might automate certain processes, but it will always require that creative spark, that unique voice. The question will be less about “how to make music” and more about what music you want to make and express. That’s what I’m excited to keep sharing with others.

You’ve mentioned a few composers you admire. Could you share a few names of composers who inspire you or whose work you enjoy?

Madison Willing: I’m really into genre-defying artists. Laurel Halo’s work is incredible, and I love Mica Levi’s releases on Hyperdub. Kode9’s label has some fantastic stuff, too. Recently, I saw Lucinda Chua and Galya Bisengalieva playing with the LCO at the Barbican, which was amazing. Galya was doing this really creative setup with her violin and guitar pedals. It’s those unexpected, boundary-pushing artists that really inspire me.